Dear Flannery,

I have this memorized: “. . . to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost-blind you draw large and startling figures.” It is your explanation of why you wrote like you did, “. . . forced to take ever more violent means to get [your] vision across to this hostile audience.” In the days before I met you, I was a member of that hostile audience, one of those who needs to be hit over the head with a sledgehammer in order for anything of lasting value to get in. I found you at just the right time, when God had suffered that my soul undergo that violence and was at last laid open to hear and see truth wherever it happened to show itself.

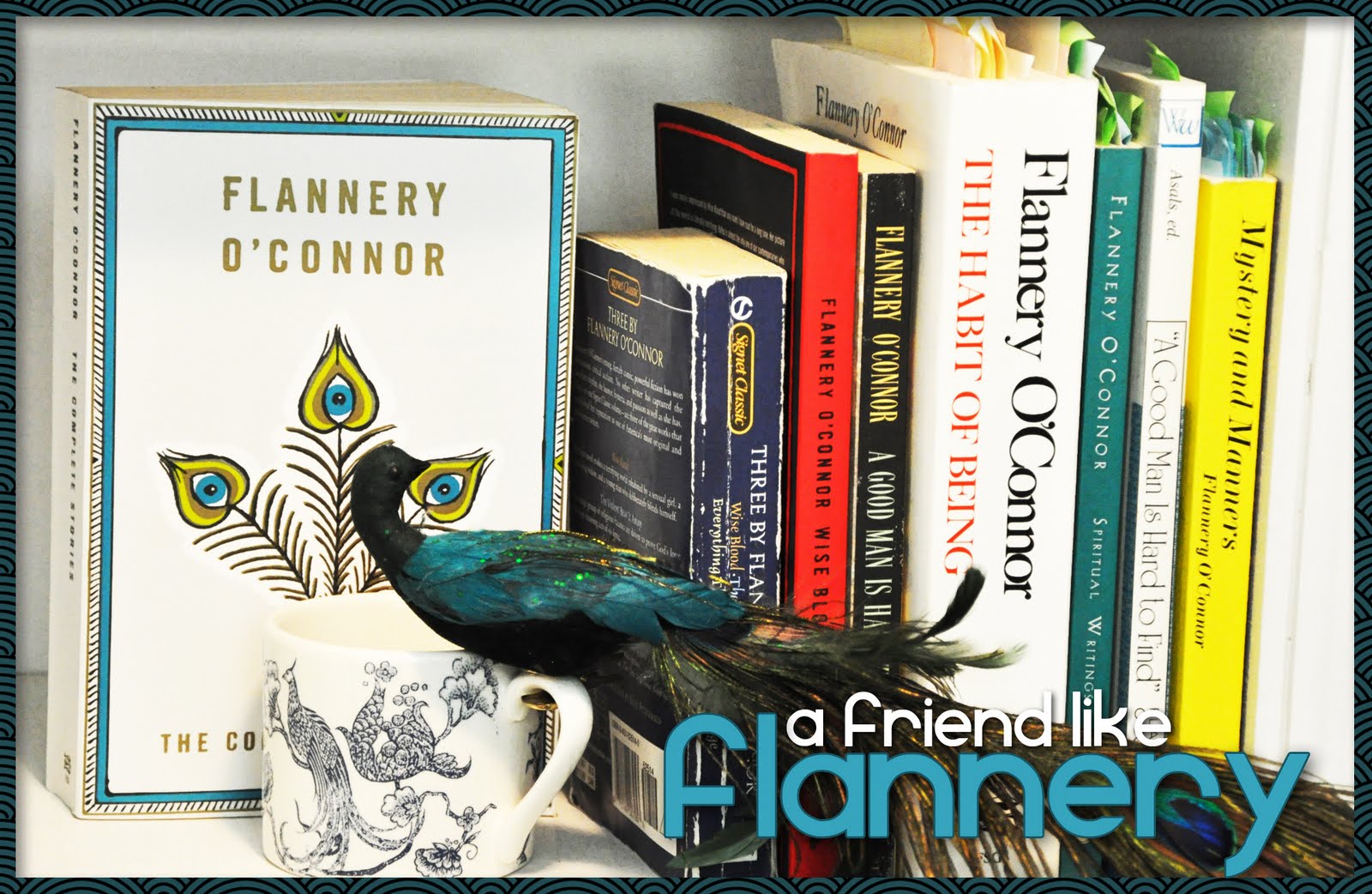

I purposely entered one of those fancy bookstores with the coffee shop in it to find your story assigned by Elizabeth Kantor and found it in a navy blue paperback called Three by Flannery O’Connor. The collection edition has what I soon learned was somewhat misleading modern art on the cover—earth-toned, sinewy, effusive figures divided by skin color—from a panel from The Arts of Life in America: Arts of the South. Of course your stories do take place in the South but are not about region or race, and do not end with earthly sufferings and strivings. You put your characters in that inordinately complex place we call the South to give them a sense of the concrete, to make them live. But these people you wrote about are all of us, inside, everywhere.

After reading the story, “Everything That Rises Must Converge,” I started at the beginning of the book with your first novel, Wise Blood. Talk about a sledgehammer to the soul! Now I have read this novel at least three times. Every time I read the last page I feel I must read the whole book again to make sure I understand what that Hazel Motes was really about.

Yours truly,

Another Christian malgre lui (in spite of herself)

No comments:

Post a Comment