Dear Flannery,

I have this memorized: “. . . to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost-blind you draw large and startling figures.” It is your explanation of why you wrote like you did, “. . . forced to take ever more violent means to get [your] vision across to this hostile audience.” In the days before I met you, I was a member of that hostile audience, one of those who needs to be hit over the head with a sledgehammer in order for anything of lasting value to get in. I found you at just the right time, when God had suffered that my soul undergo that violence and was at last laid open to hear and see truth wherever it happened to show itself.

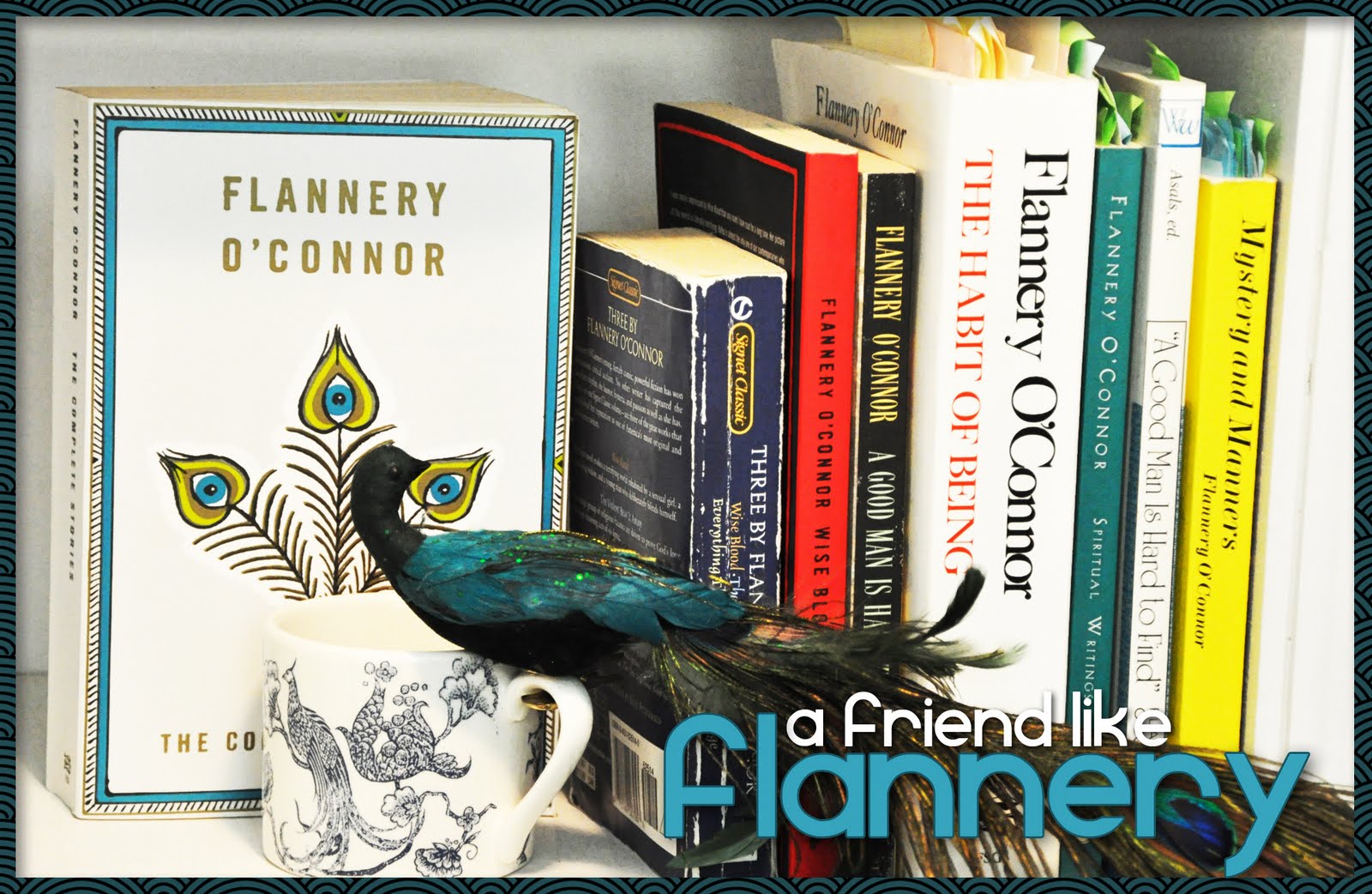

I purposely entered one of those fancy bookstores with the coffee shop in it to find your story assigned by Elizabeth Kantor and found it in a navy blue paperback called Three by Flannery O’Connor. The collection edition has what I soon learned was somewhat misleading modern art on the cover—earth-toned, sinewy, effusive figures divided by skin color—from a panel from The Arts of Life in America: Arts of the South. Of course your stories do take place in the South but are not about region or race, and do not end with earthly sufferings and strivings. You put your characters in that inordinately complex place we call the South to give them a sense of the concrete, to make them live. But these people you wrote about are all of us, inside, everywhere.

After reading the story, “Everything That Rises Must Converge,” I started at the beginning of the book with your first novel, Wise Blood. Talk about a sledgehammer to the soul! Now I have read this novel at least three times. Every time I read the last page I feel I must read the whole book again to make sure I understand what that Hazel Motes was really about.

Yours truly,

Another Christian malgre lui (in spite of herself)

Wednesday, December 29, 2010

Monday, December 20, 2010

Letter #5

Dear Flannery,

What I really mean by you being dead is that you have passed on to another realm of existence where you are busily engaged in what is most important because that is the kind of person you were here and I’m certain we don’t change from here to there but remain the same sort of person with the same feelings and wishes and beliefs. You thought so too when you said “those qualities least dispensable” in our personalities here are the ones we “will have to take into eternity” with us.

I don’t want you worrying that I’m going to track you down first thing when I get to where you are. That is not what I mean to do. Oh, sure, there are a lot of dead authors I’d like to thank or meet or know, but I don’t think this is how it will be. I think, in the Most Hopeful Place in question, among those there, all of what is thought of as admiration and appreciation for each other will automatically bounce right off us previously mortal people and land squarely on the Right Being.

I also don’t want you worrying about my being obsessed with these things, in the way the world thinks of being obsessed with religion. No, I don’t keep peacocks like you did, but I do have plenty of other interests (even though I admit they all point back to what I care most about).

You should see it now, the world I mean. The badness part is all so much more of what you described. You hit so many nails right on their heads, and like you said about St. Thomas, I wish you “were handy to consult about this” or that business. Be that as it may, I must remember to pray more. I am not consistently good at clear-minded substantial lengthy private praying. You said you weren't much good at it either if I recall. "My attention is always very fugitive," is how you put it. I can relate, my mind ends up wandering so. And the time I spend on my knees often ends up a mishmash of human wonderment in my head. But it still feels like prayer and light to me so I don't fret about it.

Wishing you were here,

Your Striving Friend

What I really mean by you being dead is that you have passed on to another realm of existence where you are busily engaged in what is most important because that is the kind of person you were here and I’m certain we don’t change from here to there but remain the same sort of person with the same feelings and wishes and beliefs. You thought so too when you said “those qualities least dispensable” in our personalities here are the ones we “will have to take into eternity” with us.

I don’t want you worrying that I’m going to track you down first thing when I get to where you are. That is not what I mean to do. Oh, sure, there are a lot of dead authors I’d like to thank or meet or know, but I don’t think this is how it will be. I think, in the Most Hopeful Place in question, among those there, all of what is thought of as admiration and appreciation for each other will automatically bounce right off us previously mortal people and land squarely on the Right Being.

I also don’t want you worrying about my being obsessed with these things, in the way the world thinks of being obsessed with religion. No, I don’t keep peacocks like you did, but I do have plenty of other interests (even though I admit they all point back to what I care most about).

You should see it now, the world I mean. The badness part is all so much more of what you described. You hit so many nails right on their heads, and like you said about St. Thomas, I wish you “were handy to consult about this” or that business. Be that as it may, I must remember to pray more. I am not consistently good at clear-minded substantial lengthy private praying. You said you weren't much good at it either if I recall. "My attention is always very fugitive," is how you put it. I can relate, my mind ends up wandering so. And the time I spend on my knees often ends up a mishmash of human wonderment in my head. But it still feels like prayer and light to me so I don't fret about it.

Wishing you were here,

Your Striving Friend

Tuesday, December 14, 2010

Letter #4

Dear Flannery,

I suppose you could call these posthumous fan letters. And yet I’m not one to write fan letters, although I confess I did write a brief note to Madeleine L’Engle after I read A Circle of Quiet many years ago, and one to Ann Lamott after I read Bird by Bird. Madeleine’s book started me on understanding my existence (an ongoing quest), and Ann’s writing was just so outrageously fresh and daring that I had to let her know I admired it (even though secretly I didn’t fully appreciate her overuse of certain four-letter words). Generally, I am not the fan type. Even though there are many human efforts I think are very fine, as life goes on I get more cautious about idolizing my fellow human beings. You make it abundantly clear that you wouldn’t want to be idolized. You’d be the first to say that none of us are very wise or pure or good, as Voltaire pointed out. So yes, a good man is hard to find. And no, it’s not fan letters I wish to write.

As I wrote in my last letter, I have read everything I know of written by you that has been published, while you lived and after. Now I am methodically reading and rereading everything again along with an added dimension or two. Not only do I trust that with further study any confusion will lessen and any understanding increase (it must, mustn’t it?), but this time I am going to be writing to you what I think about it all. What I want is someone with whom I can discuss what to me are matters of life and death to my heart's content.

Here is a hypothetical question. If you could have a new friend, and you could choose this friend from all the human beings in the world, alive or dead, ancient or modern, young or old, famous or infamous, possessing whatever degree of human intelligence, knowledge, or talent that appealed to you, whom would you choose? From what I've read, I’m guessing you’d choose St. Thomas Aquinas (whom I intend to attempt to study; I bought a fat book of his introductory works). As for me, I have cast about the whole wide timeless world for the new friend I would choose, and I am choosing you.

This is no small thing. You are a very hard person to keep up with. I think of your depth of conviction and your unswerving confidence in the direction of your work. And the books you read -- I'll have to read them all. Yes, I’m sure I’ve bitten off more than I can chew. But oh, to be able to chew even a bit of it.

C. S. Lewis wrote, “Friendship must be about something, even if it were only an enthusiasm for dominoes or white mice . . . . A Man who agrees with us that some question, little regarded by others, is of great importance can be our Friend,” and I am taking him at his word.

It appears that you valued your friends, dead or living, new and old, a great deal. Remember when you first wrote to your new friend, Elizabeth Hester, referred to as “A” in The Habit of Being?

I am very pleased to have your letter. Perhaps it is even more startling to me to find someone who recognizes my work for what I try to make it than it is for you to find a God-conscious writer near at hand . The distance is 87 miles but I feel the spiritual distance is shorter . . . . You were very kind to me and the measure of my appreciation must be to ask you to write me again. I would like to know who this is who understands my stories.

I was very glad when I read this. I had wondered if you had friends who truly understood your stories, aside from the remarkable writing, all the publishment and praise of men, and an admiring, albeit benighted, public. I imagine “A” was very smart— you continued to correspond for nine years, until you passed on, even though she converted to and then unconverted from your church— but your reaction to her letter led me to hope that you wouldn’t have minded one from me. To some significant and everincreasing degree, I do hope I understand your stories.

In mortality you liked to write letters. So do I. Hence, this is how our friendship will look. I will write you letters and since you are dead you won’t write back. But it will be better than nothing. And so I sign this letter—

Both posthumously and presumptuously,

A Friend

I suppose you could call these posthumous fan letters. And yet I’m not one to write fan letters, although I confess I did write a brief note to Madeleine L’Engle after I read A Circle of Quiet many years ago, and one to Ann Lamott after I read Bird by Bird. Madeleine’s book started me on understanding my existence (an ongoing quest), and Ann’s writing was just so outrageously fresh and daring that I had to let her know I admired it (even though secretly I didn’t fully appreciate her overuse of certain four-letter words). Generally, I am not the fan type. Even though there are many human efforts I think are very fine, as life goes on I get more cautious about idolizing my fellow human beings. You make it abundantly clear that you wouldn’t want to be idolized. You’d be the first to say that none of us are very wise or pure or good, as Voltaire pointed out. So yes, a good man is hard to find. And no, it’s not fan letters I wish to write.

As I wrote in my last letter, I have read everything I know of written by you that has been published, while you lived and after. Now I am methodically reading and rereading everything again along with an added dimension or two. Not only do I trust that with further study any confusion will lessen and any understanding increase (it must, mustn’t it?), but this time I am going to be writing to you what I think about it all. What I want is someone with whom I can discuss what to me are matters of life and death to my heart's content.

Here is a hypothetical question. If you could have a new friend, and you could choose this friend from all the human beings in the world, alive or dead, ancient or modern, young or old, famous or infamous, possessing whatever degree of human intelligence, knowledge, or talent that appealed to you, whom would you choose? From what I've read, I’m guessing you’d choose St. Thomas Aquinas (whom I intend to attempt to study; I bought a fat book of his introductory works). As for me, I have cast about the whole wide timeless world for the new friend I would choose, and I am choosing you.

This is no small thing. You are a very hard person to keep up with. I think of your depth of conviction and your unswerving confidence in the direction of your work. And the books you read -- I'll have to read them all. Yes, I’m sure I’ve bitten off more than I can chew. But oh, to be able to chew even a bit of it.

C. S. Lewis wrote, “Friendship must be about something, even if it were only an enthusiasm for dominoes or white mice . . . . A Man who agrees with us that some question, little regarded by others, is of great importance can be our Friend,” and I am taking him at his word.

It appears that you valued your friends, dead or living, new and old, a great deal. Remember when you first wrote to your new friend, Elizabeth Hester, referred to as “A” in The Habit of Being?

I am very pleased to have your letter. Perhaps it is even more startling to me to find someone who recognizes my work for what I try to make it than it is for you to find a God-conscious writer near at hand . The distance is 87 miles but I feel the spiritual distance is shorter . . . . You were very kind to me and the measure of my appreciation must be to ask you to write me again. I would like to know who this is who understands my stories.

I was very glad when I read this. I had wondered if you had friends who truly understood your stories, aside from the remarkable writing, all the publishment and praise of men, and an admiring, albeit benighted, public. I imagine “A” was very smart— you continued to correspond for nine years, until you passed on, even though she converted to and then unconverted from your church— but your reaction to her letter led me to hope that you wouldn’t have minded one from me. To some significant and everincreasing degree, I do hope I understand your stories.

In mortality you liked to write letters. So do I. Hence, this is how our friendship will look. I will write you letters and since you are dead you won’t write back. But it will be better than nothing. And so I sign this letter—

Both posthumously and presumptuously,

A Friend

Monday, December 13, 2010

Letter #3

Dear Flannery,

It’s about time I let you in on how you and I came to be introduced. I had lately decided that with what schooling I did have and the type it was and the age in which it occurred, I had in large part missed out on a classical education and was setting out to fashion one for myself. To begin, I was exploring the best books about reading the best books. Along with Clifton Fadiman's The New Lifetime Reading Plan, I got my hands on The Politically Incorrect Guide to English and American Literature by Elizabeth Kantor (2006), and was finding it wonderfully illuminating. She tells us what’s gone wrong with higher education today and provides a plan to amend the literary wrongs done us. It was as if Elizabeth said (like my dad used to say as he switched on a lamp when he found me reading in a darkening room),“Would you like some light on the subject?”

On page 169 in a big gray text box is “A Mini-Course in American Literature,” what the author calls “a high-speed tour through our whole literature by reading bite-sized pieces of fine American writing from Edgar Allan Poe to Flannery O’Connor.” (Aren't you pleased?) I was to read four tiny poems, five short stories, and two novels. I decided to make my way through this list in a highly conscientious manner. Your “Everything that Rises Must Converge” was one of the short stories, and that’s how we met. (You will surmise correctly that your stories. or parts of them, are now thought of as politically incorrect, but it seems you knew that when you wrote them.)

That one brilliant story intrigued me enough to keep reading until I had read all your fiction. And then, because I wanted to know if I was really "getting" any of it or not, I read your papers and speeches and letters, all that they’ve put into books. My copies of these collections are scribbled on with underlinings and notes and exclamation points and question marks and stuffed with a wild variety of colorful bookmarks and sticky Post-it notes, so many that they don’t do me any good. But I can’t help myself. Every time I open one of these books I find something more to mark or exclaim at or make notes on. I must take it slow or go blind from the brightness.

Yours out of the gloom,

A Reader

It’s about time I let you in on how you and I came to be introduced. I had lately decided that with what schooling I did have and the type it was and the age in which it occurred, I had in large part missed out on a classical education and was setting out to fashion one for myself. To begin, I was exploring the best books about reading the best books. Along with Clifton Fadiman's The New Lifetime Reading Plan, I got my hands on The Politically Incorrect Guide to English and American Literature by Elizabeth Kantor (2006), and was finding it wonderfully illuminating. She tells us what’s gone wrong with higher education today and provides a plan to amend the literary wrongs done us. It was as if Elizabeth said (like my dad used to say as he switched on a lamp when he found me reading in a darkening room),“Would you like some light on the subject?”

On page 169 in a big gray text box is “A Mini-Course in American Literature,” what the author calls “a high-speed tour through our whole literature by reading bite-sized pieces of fine American writing from Edgar Allan Poe to Flannery O’Connor.” (Aren't you pleased?) I was to read four tiny poems, five short stories, and two novels. I decided to make my way through this list in a highly conscientious manner. Your “Everything that Rises Must Converge” was one of the short stories, and that’s how we met. (You will surmise correctly that your stories. or parts of them, are now thought of as politically incorrect, but it seems you knew that when you wrote them.)

That one brilliant story intrigued me enough to keep reading until I had read all your fiction. And then, because I wanted to know if I was really "getting" any of it or not, I read your papers and speeches and letters, all that they’ve put into books. My copies of these collections are scribbled on with underlinings and notes and exclamation points and question marks and stuffed with a wild variety of colorful bookmarks and sticky Post-it notes, so many that they don’t do me any good. But I can’t help myself. Every time I open one of these books I find something more to mark or exclaim at or make notes on. I must take it slow or go blind from the brightness.

Yours out of the gloom,

A Reader

Letter #2

Dear Flannery,

I didn’t read your stories or novels until I was as old as they were, that’s half a century, or couldn’t remember if I had. But it’s just as well because before everything important inside me began to change I wouldn’t have understood them. Back then I’m afraid I would have reacted like a great many people reacted when your stories were new and how it seems most still react today. No, I wouldn’t have written you the kind of letter you got from the old lady in California who said that a person who comes home from work at night wants to read “something that will lift his heart,” implying that your stories had not lifted hers. In those days I had plenty of respect for published material just because it was published and I wouldn’t have presumed to tell a famous author what to do. But your meanings would have gone over my head, missing my heart by a mile.

Actually, it’s getting difficult to imagine what I would have thought in the days before everything changed. It’s almost impossible. I seem to be forgetting some of what or how I used to think before ten years ago. The new is doing its best to blot out the old, and in some ways that is good, but I know I must remember it all--- with gratitude.

I must say, though, that I just read your story, “The Lame Shall Enter First,” once again, and knowing beforehand the horrible thing that was going to happen at the end, could only manage it in the light of day. That one does that to me. The consequences of unchecked human nature can be so frightening and tragic. But Sheppard, even he, the false shepherd, the false, self-appointed savior, did finally, at the very end, experience a mighty, wrenching shift inside, and that’s the greatest, most wonderful miracle of all. I like how Leif Enger describes a real miracle: "no cute thing but more like the swing of a sword." Still, you described it more completely as: grace that “cuts with the sword Christ said he came to bring.”

With a lifted heart,

A Reader

I didn’t read your stories or novels until I was as old as they were, that’s half a century, or couldn’t remember if I had. But it’s just as well because before everything important inside me began to change I wouldn’t have understood them. Back then I’m afraid I would have reacted like a great many people reacted when your stories were new and how it seems most still react today. No, I wouldn’t have written you the kind of letter you got from the old lady in California who said that a person who comes home from work at night wants to read “something that will lift his heart,” implying that your stories had not lifted hers. In those days I had plenty of respect for published material just because it was published and I wouldn’t have presumed to tell a famous author what to do. But your meanings would have gone over my head, missing my heart by a mile.

Actually, it’s getting difficult to imagine what I would have thought in the days before everything changed. It’s almost impossible. I seem to be forgetting some of what or how I used to think before ten years ago. The new is doing its best to blot out the old, and in some ways that is good, but I know I must remember it all--- with gratitude.

I must say, though, that I just read your story, “The Lame Shall Enter First,” once again, and knowing beforehand the horrible thing that was going to happen at the end, could only manage it in the light of day. That one does that to me. The consequences of unchecked human nature can be so frightening and tragic. But Sheppard, even he, the false shepherd, the false, self-appointed savior, did finally, at the very end, experience a mighty, wrenching shift inside, and that’s the greatest, most wonderful miracle of all. I like how Leif Enger describes a real miracle: "no cute thing but more like the swing of a sword." Still, you described it more completely as: grace that “cuts with the sword Christ said he came to bring.”

With a lifted heart,

A Reader

Monday, September 13, 2010

Letter #1

Dear Flannery,

I read your story, "Greenleaf," again last night. At the end, it seemed I had been holding my breath and when I finally breathed out my soul emptied itself of everything it didn’t need, and then felt wonderfully fresh and small, just the right size, and enriched somehow. It was as if it were suddenly concentrated down, full strength, like frozen orange juice.

All of your stories, which I read and reread from time to time, tend to have the same distilling effect on me, as far as I have come to grasping them, but there are four I loved best right from the start, and "Greenleaf "is one of those. I mean, she gets gored through the heart, if that isn’t the most wonderful thing (you know what I mean). The first time I read it, now going on four years ago, I had to reach over and poke my husband awake and read the two last paragraphs again out loud to him and he said it was wonderful, too. (He's sweet the way he tries to wake up for important things.) I think your stories are transcendent. They mean something huge.

Lately I have been reading for the first time lots of short works---by Henry James and Edith Wharton and Thomas Hardy and Franz Kafka, and more --- and they are very good. I especially like what Joseph Conrad seems to be saying but his style is terribly difficult for me to wade through, still, I plan on reading more of him. Of course James Joyce sure could write but so far I have found him more cynical than having anything to say of any value, but then I’ve only read The Dubliners so far. (I would be tossed out of any college English class for saying that, I know.) Anyway, great as these famous stories may be, I don’t like any of them as well as yours for how they speak to my infant soul. As Conrad said, they make me hear, feel, see, and find “that glimpse of truth for which [I] have forgotten to ask.”

Still concentrating,

A Reader

I read your story, "Greenleaf," again last night. At the end, it seemed I had been holding my breath and when I finally breathed out my soul emptied itself of everything it didn’t need, and then felt wonderfully fresh and small, just the right size, and enriched somehow. It was as if it were suddenly concentrated down, full strength, like frozen orange juice.

All of your stories, which I read and reread from time to time, tend to have the same distilling effect on me, as far as I have come to grasping them, but there are four I loved best right from the start, and "Greenleaf "is one of those. I mean, she gets gored through the heart, if that isn’t the most wonderful thing (you know what I mean). The first time I read it, now going on four years ago, I had to reach over and poke my husband awake and read the two last paragraphs again out loud to him and he said it was wonderful, too. (He's sweet the way he tries to wake up for important things.) I think your stories are transcendent. They mean something huge.

Lately I have been reading for the first time lots of short works---by Henry James and Edith Wharton and Thomas Hardy and Franz Kafka, and more --- and they are very good. I especially like what Joseph Conrad seems to be saying but his style is terribly difficult for me to wade through, still, I plan on reading more of him. Of course James Joyce sure could write but so far I have found him more cynical than having anything to say of any value, but then I’ve only read The Dubliners so far. (I would be tossed out of any college English class for saying that, I know.) Anyway, great as these famous stories may be, I don’t like any of them as well as yours for how they speak to my infant soul. As Conrad said, they make me hear, feel, see, and find “that glimpse of truth for which [I] have forgotten to ask.”

Still concentrating,

A Reader

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)